J. Edward Slavin was a long-term elected Democratic Sheriff serving from 1935 (elected in November 1934) then again as High Sheriff in 1959, serving a total of 26 years.

Square jawed Jack Slavin told the Waterbury Republican (July 23, 1944), “Do you know that we in America have the largest jail and prison population in the world? That proves we didn’t spend money in the right place. We spent it at the top, creating large police departments and other agencies for the prevention of crime and enforcement of law and order, while we neglected the bottom where crime starts.”

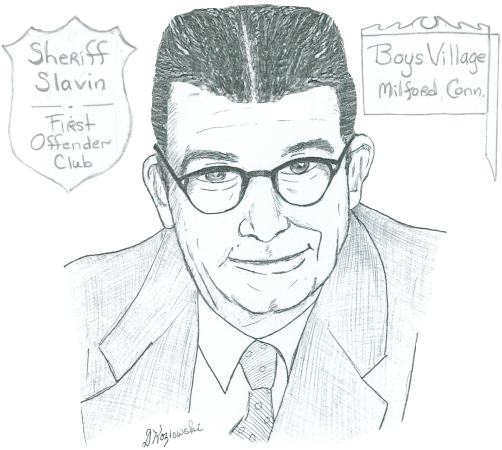

That is still true today as many point out. Sheriff Jack Slavin actually did something about it. Slavin believed that if he could intervene early enough in the lives of at-risk boys and girls they would become good, law-abiding citizens instead of law-breaking criminals who were an expense to society. To that end Jack created the First Offender Club in 1937. Youth who joined received a pledge card, a nickel- plated badge, and monthly newsletter. He promoted it in newspaper stories across the country, and a weekly coast-to-coast radio program heard on the Mutual radio network. More than 30,000 children took the pledge not to become a first offender or get a police record and to cooperate with authority figures.

Slavin turned to Hollywood to spread his message. Columbia Pictures produced in 1939 “First Offenders” based on Slavin’s screenplay of a hard nosed District Attorney dedicated to “Stop turning kids without a chance into men without hope!” The Movie debuted at the Loews-Poli Theater in New Haven to a massive crowd. The nationwide movie ads included contact information directly to the Slavin so that boys could reach him with their problems for personal counsel. He got back to the hundreds who wrote.

Jack did not stop there. He drew inspiration from the success of a residential program in Nebraska founded by Father Edward J. Flanagan in 1917 which had grown into a community known as Boys Town ten miles outside of Omaha. He and a dedicated team including Yale Star Albie Booth, former New Haven Jailer Wm.F. Hayes, 4-H member Stanley Konykowski and housing and trucking magnates Peter Juliano and Dan Adley.

To put their plan into effect Slavin offered to buy Charles Island from the Dominican Brotherhood which had a retreat off the Milford coast there. Before the sale could be consummated, the “Long Island Clipper” hurricane of 1938 devastated their buildings. Not deterred, the group purchased 82 acres on Wheeler’s Farms Road in 1941.

Boys Village was established the following year with Jack serving as their first president. Its doors opened in 1944. It initially operated as a summer camp and became a year- round facility in 1947. With a 14-room farmhouse, small cottage, cornfield, potato patch, dairy barn, and poultry buildings, it was originally designed to accommodate 16 boys who were 10 years old and older.

Patterned after a New England village, and of course Boy’s Town, it offered communal living, educational and training facilities for industry and farming, and a psychological clinic. The boys grew most of the food they ate and were responsible for performing chores around the facility. In1948 the board of directors made plans to accommodate a total of 31 boys.

Not everyone was pleased that “troubled boys” would be joining their neighborhood. NIMBY is not a new concept. Slavin stood firm however, pointing out to the Hartford Courant (1/2/1942) that his facility would be “... neither a penal institution nor a reform school. The fair-minded citizens of Milford, where I have been a resident and voter for nearly a quarter of a century, I believe, have confidence enough in me and know me well enough to know that I would not bring anything to Milford that would not be an asset to that beautiful town.” So much for that. His re-election as Sheriff proved his point.

Slavin’s oft-stated goal was “to provide a village of opportunity for the homeless boy, where he may develop a spirit of self respect, a love for work, and a desire to forge ahead through honest industry. ... I really believe all boys have good in them if they are shown the right way. I always believed that if you keep a boy busy he won’t get into trouble. I’m not interested in how much it costs to grow a boy. I’m interested in what kind of boy he’ll make.” He spelled out in Boys’ Village: A Home for Homeless Boys (1943) the goals of Boys Village:

-

To establish and conduct a farm for boys on a plan sufficiently extensive to afford instructions.

-

To restore handicapped and homeless boys in need of care and protection to a normal life wherever possible through a carefully planned and executed manner, involving relief, employment, medical care and education. To establish and conduct a place for the social betterment of young boys.

-

To establish, maintain and provide a place for young boys so asto give them an opportunityto grow and develop in “social usefulness.”

The village was designed to operate differently from the more traditional homes for boys. An early Boys Village publication described the experience: “The one inflexible rule of Boys’ Village is that its boys shall not be regimented. The atmosphere is personalized and homelike, and the boys are guided rather than compelled by a trained staff. The boys live normally and wholesomely, with personal interests, possessions and friends, and they attend the churches of their choice and the Milford public schools where many of them are at the head of their classes. A sense of responsibility and self- sufficiency is developed in them to a far greater extent than is possible in “institutionalized” homes.”

Slavin under the auspices of Boys Village published several comic books in 1945 under the banner “Courage Comics.” The theme of the stories was courage in the face of adversity featuring crime, athletics, and heroism in World War II. Characters included U.S. Navy Lieutenant Chick Courage, boxer K.O. Brown, and a dog named Red Badge. One recurring character was self modeled. “Sheriff Jack” would save young offenders from a jail and exposure to hardened criminals. He dissuaded them from pursuing a life of crime by taking them under his wing and join the First Offender Club.

Slavin stepped down in 1947 but not out. Foreshadowing “Scared Straight” programs of today, Slavin outfitted a bus with exhibits in a traveling crime- education center he called “Jail on Wheels.” Displayed were tools used by police including fingerprints, recording devices, forensics, a lie detector, and means of restraint and punishment such as a reproduction jail cell and an electric chair identical to that used at Wethersfield for executions. The Mansfield News-Journal (Ohio) reported (11/12/1948) “Slavin ... is firm in his belief that, if a youngster sits in an electric chair and puts the leg irons around his calves and the steel cap on his head, he will never forget what the reward is for high achievement in the world of crime.”

Donations from more than a million people visitors in its first year covered expenses. Slavin paid off the remaining debts for Boys Village and put a second Jail on Wheels out on the road. Human services agencies from around Connecticut made requests on behalf of another 150 boys so plans for a badly needed expansion of Boys Village were undertaken.

Over the years, Boys Village has continued to seek ways to serve children with emotional and behavioral needs. It has been re- named Boys & Girls Village and is still at its original site on Wheelers Farms Road. Its services and reach have grown with the addition of a second campus in Bridgeport. It is still committed to the tradition begun by its founders of providing warmth, guidance, and life-training for children at risk of being forgotten.