2008 inductee

Ansantawae

Imagine the small coastal town of Milford, Connecticut inhabited only by Native Americans. The Wepawaug tribe, a branch of the larger Paugasset tribe resided in what is now Milford and Orange. Ansantawae the chief or sachem of the Wepawaug Indians along with his tribal council controlled the Indian village. Life was lived simply in small wigwams made of sticks and leaves, currency did not exist, nature provided much of their food, and English settlers had not set foot upon the land now Milford as of 1637. This all changed during the reign of King Charles I when increasing numbers of English people migrated to New England because they no longer accepted of the Church of England and were persecuted for their non-conformity (Harrington 2).

The Wepawaug tribe lived in present day Milford sites that were full of resources, mainly along the shoreline. Villages were set up at Charles Island, Indian Point presently (Gulf Beach), Poconoe Point( presently Laurel Beach), the Wepawaug River and Oyster River (Teachers 13). Their seaside location made Ansantawae’s tribe largely dependent on fishing, especially shellfish such as oysters and clams that flooded the shoreline. Milford residents still use the Sound shore as an important and abundant resource (DeForest 50). Large heaps of shells found along Milford’s coast give evidence of the Indians reliance on the water and its life (DeForest 50). Nevertheless Ansantawae’s tribe did not rely solely on Long Island Sound as a resource, as land was plentiful too. Milford’s wildlife proved bountiful with pigeons, quails, turkeys, partridges, cranes, geese, ducks and beavers to hunt for food, skins, and feathers. Though the Wepawaugs did not largely depend on agriculture, they were able to grow maize, tobacco and beans to support themselves. They also were known for gathering strawberries, blueberries and blackberries (Teachers 16). Ansantawae and his tribe were successful in drawing a healthful diet from the bountiful lands around the Wepawaug.

In May of 1637 the “Hector” sailed from London to Boston carrying John Davenport, Theophilus Eaton and others from London. It was followed by another ship weeks later carrying many of the original English settlers of Milford, including Robert Treat, John Sherman, Thomas Tibbals, John Fletcher and led by Peter Prudden (Harrington 2). Although they remained in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for almost a year, Davenport and Prudden had from the start desired to establish their own colony. In August 1637 on an expedition during the Pequot War, the region at the mouth of the Quinnipiac River in Connecticut was discovered and marked as a potential location for settlement. Davenport and company decided this was the place to settle their colony which would later become present day New Haven (Harrington 3). After the Pequot war, as the Connecticut and Massachusetts militia began to pursue the remnants of the Pequot tribe along the Connecticut coast, Sergeant Thomas Tibbals noticed the region above the mouth of the Wepawaug River. Using an old Indian trail that is today the Boston Post Road, Tibbals and his troops explored the area that is today Milford and appraised it as an ideal spot for settlement (Harrington 1).

On February 12, 1639 Edmund Tapp, William Fowler, Benjamin Fen, Zachariah Whitman and Alexander Bryan from New Haven journeyed to the area that Tibbals had explored ten miles west of the New Haven Colony and told Ansantawae and his tribe that they wished to purchase the Wepwaug land (Harrington 3). Ansantawae held a council with his tribe and together they decided to sell the land. As chief, Ansantawae was privileged to do what he wanted provided it would be for the good of the tribe (Teachers 14). Though convinced that selling the land to the English would benefit the Wepawaug tribe, Ansantawae still wanted the council’s support for such an important decision. The English settlers purchased the land ten miles southwest of the Quinnipiac River and all the land between the East and Housatonic Rivers for its eastern and western borders (Teachers 13), and Long Island Sound north to the “two mile brook” the land between Milford and Derby, (Harrington 2) for its southern and northern borders. The English settlers paid Ansantawae and the Wepawaugs six coats, ten blankets, one kettle, twelve hatchets, twelve hoes, two dozen knives, and a dozen small mirrors (Teachers 13). Ansantawae’s signature on the deed of the land was represented by a bow and arrow. Handing over the land was symbolized by the old English tradition of the “turf and twig” ceremony. Ansantawae along with his council Anshuta, Manamatque, Tatacenacouse and Aracowset took part in this ceremony (Teachers 14). The English gave Ansantawae and his men a piece of turf along with a stick, and they proceeded to stick the twig in the turf to symbolize the handing over of the land from the Indians to the English. Later on, in 1656, another considerable tract the settlers bought for twenty-six pounds; and three or four years subsequently, Indian Neck, lying between East River and the sound generally from present day Woodmont to Milford Harbor was purchased for twenty-five pounds (DeForest 269). A reservation was made by the Indians of twenty acres on the neck of the area near present day Gulf Beach, but they sold it about a year after for six coats, two blankets and a pair of breeches (DeForest 271). The Indians sold the land around the Wepawaug River in the hope that they would gain English protection against the Mohawks, who were continually raiding their territory (Harrington 5). The only land that remained in the ownership of the Wepawaugs and Ansantawae were their sacred sites of Charles Island and Gulf Beach.

During Ansantawae’s reign war broke out between the tribe and the Mohawks. (Teachers 18). Wars were common between these tribes. Before commencing with battle, ambassadors were sent to the enemy or sometimes a general council was held in preparation for the war (Teachers 18). In 1645 the Mohawks attacked the Wepawaug tribe. Fires were set around Milford causing the Wepawaugs and local wildlife to suffer. Ansantawae, as head of the tribe, led a large war party and pushed the Mohawks back (DeForest 239). The Mohawks returned in 1648, and in a swamp located near Wildermere Beach they hid themselves in an attempt to surprise the Wepawaugs. Luckily for Ansantawae and his tribe the English accidently discovered the Mohawks in the swamp and were able to notify the Wepawaugs of the Mohawks’ presence (DeForest 239). Since the English discovered the Mohawks prior to their planned attack, the Wepawaugs were able to raise a large force of armed men and successfully defeat the Mohawks.

There is a famous Milford story that tells of the Mohawk whom the Ansantawaes tied to a pole for the mosquitoes to eat alive. Thomas Hine, a Milford resident, found the Indian captive, gave him food and clothing, escorted him to the Housatonic River, put him in a boat and sent him on his way (Teachers 19).The Mohawks were well known for attacking the Wepawaug tribe on multiple occasions.. The Wepawaugs’ fort in Milford survived this attack in 1648, but was later destroyed in 1671 by the Mohawks (DeForest 269).

Of the places that the Wepawaugs still controlled, Ansantawae lived the remainder of his life on Charles Island along with his wife and sons in “the big wigwam” (Teachers 14). The Wepawaug Indians regarded the island as sacred ground (Guide 1). Although referred to as Charles Island today, it was once called Poquahaug by the Wepawaugs (The Curse 1). Ansantwaes’ lodge on Charles Island was richly furnished with furs, for whenever warriors or braves went hunting they brought their chief the prizes of their hunt (Teachers 14). The Wepawaugs were later lead by Ansantawae’s sons Tountonemoe and Ackenach. Tountonemoe died around about 1660 and Ackenach succeeded him (DeForest 269). After decades of controlling what is today southern New Haven County, Charles Island and Gulf Beach were the only land left to the Wepawaugs by the 1670’s.

Today Milford, Connecticut is the 6th oldest town in Connecticut thanks to the purchase of the Wepawaugs’ land by English settlers. The town now blooms with a population of 53,045 people mostly descendents of European immigrants.(Milford, CT profile). The Wepawaug tribe is remembered throughout Connecticut by the Wepawaug River that rises from Woodbridge and flows down to the sound through our town of Milford. The Masonic Lodge on the Milford green is named after the Wepawaugs’ great Chief Ansantawae, keeping the memory of the first leader of Milford, Connecticut alive

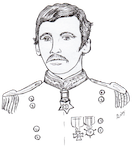

George Wiliam Baird

George William Baird is one of the first five local notables inducted into the Milford Hall of Fame. George William Baird was born December 30, 1839 in Milford, Connecticut.

His ancestry in America dates back to 1639, and includes in his father’s family line Captain John Beard, a soldier in the defense of Connecticut against the Indians. His family on his father’s side is descended from Thomas Hooker, the founder of the Connecticut Colony (Gates 119). His father, Jonah Newton Baird was a farmer who died while George was very young. It was his mother, Minerva Gunn Baird, who George owed all the success in his life to because she made him into the man that any soldier would want to follow (Gates 120).

Born in 1839, George formed habits of hard work when he was young because a strong constitution enabled him to begin work on the farm when he was only nine years old. Unoccupied time was unknown, and in the accomplishment of work he had undertaken he gained great satisfaction. Although most of his time was spent on typical farm work, reading and study were never neglected. For formal education, he attended Hopkins grammar school and graduated in 1859, entering Yale University at once which made him one of a tiny elite. In 1862, during the Civil War he enlisted as a private, but despite his absence due to military service, he received his diploma in 1863 with his class (Gates 120). Even though he devoted his life to a career in the military, he always found pleasure and recreation in the reading of history and poetry (Gates 121).

His military career began when he enlisted in the 1st Battery of Connecticut light Artillery in 1861. As a result of a competitive examination, he was promoted from the rank of private immediately to that of colonel in the volunteer army. (Gates, 120) After the appointment to colonel, he participated in several battles in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. The 1st Battery made an expedition to James Island and participated in operations against Charleston S.C. from May 31st to June 28th 1862. The major part of the expedition was the battle of Secessionville on June 16th 1862. Later he was made Colonel of the 32nd Regiment of the U.S. colored troops. The 32nd Regiment was ordered to Hilton Head S.C. in April 1864, and stood duty there until June. When the Civil War ended he decided to make a career out of the military. He completed his engineering course at Sheffield Scientific school 1866, and in May of that year he was appointed second lieutenant in the regular army and in 1871 he became the adjutant-general of his field command (Gates 121).

Baird was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions against the Nez Perce at the Bear Paw Mountains, in 1877. His medal citation reads that it was awarded “For most distinguished gallantry in action with Nez Perce Indians”. At the time of the Battle at the Bear Paw Mountains, Baird was a 1st Lieutenant. During the battle he served in the 5th Infantry Regiment nicknamed the "Bobcats". The 5th Infantry Regiment is the third-oldest infantry regiment of the United States Army, tracing its origins to 1808 (Dillon 126). It has participated in some way in most of the wars the United States has fought.

The 5th Infantry was pursuing Chief Joseph and his tribe of Nez Perce Indians. The battle started when the Nez Perce saw the 5th Infantry Regiment advancing on their position. The Indians didn’t have time to flee, but they did have enough time to fortify their position. They made trenches in the side of the mountain to slow the advance of the attacking U.S. army. Custer’s outfit, the 7th Cavalry, charged in support of the 5th Infantry but was pushed back under a barrage of arrows shot by the Indian warriors (Dillon 126). When the day was over, Colonel Nelson A. Miles, the commander of Baird’s Regiment, tried to negotiate a peace treaty with Chief Joseph. While this was going on, each side removed their wounded from the field. On October 2, the United States' 12-pound Napoleon artillery piece arrived at the battlefield (Dillon 127). The Napoleon artillery fired on the Indian trenches in hopes to force the Nez Perce to surrender, which they did (Dillon 127).

While he was giving orders and carrying notes across the battlefield, Baird was shot in the left forearm and an arrow severed his ear. He recovered well from his injuries, and in 1878 Colonel Miles recommended that he receive the Medal of Honor for his duties at the Battle of Bear Paw Mountain. Baird was presented the Medal of Honor in 1894 (Dillon 125). He was living in Milford at the time.

In conclusion, George William Baird is a great choice to exemplify what Milford wants in their citizens. Baird’s career demonstrates that even if you come from a small town, you can still make a big impact for your nation. After he retired from the military, Baird was active in his town and his church. He died November 28, 1906 at the age of sixty seven. Baird is buried in the Milford cemetery with two plaques telling what he did to earn the Medal of Honor, his grave number is 6393190 (Connelly 2).

Helen P. Langner

a trail blazer in 20th century

Helen Parthenay Langner, who resided in Milford for an impressive seventy years, is renowned for a number of reasons. As the fourth woman to graduate from the Yale School of Medicine, she was one of the few women who broke the gender barrier that barred women from the field of medicine. Passing away due to natural causes on the 10th of December, 1997 at the age of 105, the centenarian is honored as Milford’s oldest resident at the time of her death. Most well-known for her many accomplishments or remarkable traits as a person, Dr. Langner is also truly famed for her prodigious impact on the “Small City with a Big Heart.” (ObitFinder 1)

Though Langner was the only daughter of six children, she got along well with all her five younger brothers in their residence at 1 Shipyard Lane, which was demolished in 2003 due to the condominium construction. She had a close relationship with her brother Gustave, a well-known swimmer. Because they lived near the water, she took an interest in sailing on Long Island Sound. As a child, Langner enjoyed listening to operas such as the Magic Flute and Die Fledermaus. According to John Curtis, the author of “A Life of Engagement,” when Langer was at Yale University, her mother “would slip her an extra dollar to attend a performance.” Her interest in operas would lead her to listen to operas every Saturday afternoon during her later years. In addition, her favorite classical music radio station was WQXR of the New York Times. Some of her favorites included Beethoven, Mozart, and the songs of Schubert. In fact, on Sundays, she would listen to classic jazz; although she did not really like it, she wanted to know more about it. Literature also intrigued Langner. So, she attended book discussions at a public library. (Sizer 1)

According to Patricia Rosenau, the author of the article “Doctor Looks Ahead to 65th Class Reunion,” Langner graduated from the old Milford High School in 1910, the first year that the school adopted a four-year curriculum. Langner’s father was a baker, a job which produces insufficient income to sustain Langner’s college tuition; hence, financial problems were prevalent as the time came for Langner to consider college. However, she excelled in academics to such an extent that she easily entered Hunter College without taking an entrance exam. She attended Hunter because at that time, no Connecticut college had broken the gender barrier. Immediately after her graduation in 1914, she became a high school biology teacher but felt it was not her true calling. While working in an admissions office at St. Luke’s Hospital in New York City, she considered training to be a nurse. Langner’s father, on the other hand, did not approve of the idea and wanted her to return home in order to attend the Yale School of Medicine, which had then begun to accept women. Her daily routine as a Yale graduate student involved her catching an early train from Milford to New Haven and walking from the Union Station to her classes. Upon returning home in the afternoon, she would immerse herself in serious study. (Sizer 1) (Curtis 3) (Rosenau 1)

Initially, Yale claimed that “the lack of proper bathroom facilities for women” was the impetus behind the gender barrier. But eventually, Henry Farnam, a Yale graduate and professor of economics, donated money to the institution to execute “suitable lavatory arrangements” (Wortman 2). Thus, Louise Farnam, his daughter, became the first woman to graduate from the Yale School of Medicine. Just two years later in the Class of 1922, Langner became the fourth woman to do so.

Moreover, she was the only woman in her medical school class. Since she was accustomed to being surrounded by five brothers, her interaction with male classmates was amicable; as a result, she did not think back on those days with bitter resentment toward the discrimination that she received. As a matter of fact, she looked up to her male classmates. For instance, classmates and twin brothers Edward and Maurice Wakeman—though the latter died after doing research in Africa— both maintained a particularly close relationship with Langner, even after graduation. This relationship is just one example of Langner’s compatibility with others. As stated by Rosenau, Langner had said that, “The men in charge supervised you and helped you along. We discussed each case at case conferences, and that’s when you learn the most.” In fact, a Yale professor recognized her talent and asked her to serve as a surgical intern for a month, where Langner felt the adrenaline rush as she rode the ambulance three times through New Haven. (Rosenau 2) (Curtis 3) (Wortman 1-2)

Langner’s inspiration stemmed from her interest in the natural sciences—anything that dealt with how the human body worked. She helped bring greater emphasis on Science which most likely became a greater focus in the curriculum due to the influence of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which warned people in school about the dangers of alcohol. Full of passion and ambition, she engrossed herself in physics, psychology, and anything else that captivated her. Fortunately, her hobbies turned out to be beneficial when these courses became medical school requirements.

Back when she was still employed as a clerk at St. Luke’s Hospital during World War I, she had received much hands-on experience when the laboratory employees allowed her to look at slides and even watch an operation. Simultaneously, as she continued her studies, Langner developed an interest in both psychiatry and pediatrics. However, she was further drawn to the field of psychiatry after she stumbled upon Clifford Beers’ book “The Mind That Found Itself,” in which the author discussed his recovery from his mental illness. She was so engaged in the book’s content that she finished it in two nights, putting aside her academic course work. Her public health professor, who had introduced Langner to the book, also led her to a paid job at Ward’s Island, a state mental hospital in New York. There, she learned how to administer ether, an inhalant anesthetic, and quickly moved up to the highest position that a woman could attain at the time: senior assistant physician. After her work at Ward’s Island, she received a National Committee for Mental Hygiene fellowship to the clinics of Cleveland, Boston, Chicago, and New York. Langner had a clear direction in life, for she knew she wanted to set up a child guidance clinic after her residency. However, with the prevailing gender discrimination, men were always preferred for such positions. Still, she persisted. Her two-year work at a child guidance clinic of the Indiana School of Medicine came to an end as the arrival of the Depression dissolved its funds. (Rosenau 2) (Curtis 3)

As a pioneer in the field of child psychiatry, she possessed something unique that drew children to her since she was “very approachable” (Curtis 4). In one particular instance, she treated a five-year-old boy with hyperactive symptoms by encouraging his curiosity. Langner did not view the boy as a patient; instead, she allowed him to explore every corner of her house as a welcomed guest, without restricted access. Though she never had children of her own, she had special bonds with them. One of her numerous patients was a ten-year-old boy with a tendency to daydream and poor hand-eye coordination. She played games with him in order to become familiar with his strengths and weaknesses. (Curtis 4-5)

The month Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Langner opened her own private practice in New York City, where she was able to extend her influence. But, she retired from private practice in 1970 after being appointed to The New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center. With a dedicated mind, Langner worked consistently into her nineties. (Letetia 82) (Curtis 4)

After working in the medical center, she was a consulting attending physician at Milford Hospital up until 1988 at age 96, and was honored as the oldest practicing psychiatrist in Milford. During her time at the original Milford Hospital Society, it consisted of “6 beds, several nurses and general practitioners”; by 1925 there were “25 beds, an ‘accident room,’ and a small operating room” (Letetia 82). Furthermore, when Langner worked there in the 1970s, extensive additions—still present today—were added to the hospital. Due to her constant presence in Milford Hospital, she confessed, “I guess I’m an institution there” (Adler 287). Milford City Clerk Alan Jepson recalled, “To see her there was to feel all was right with the world…as long as she was in it.” Although she stopped working for pay at the age of ninety-eight, George Kraus, director of the Milford Health Department, finally convinced her to allow him to pay for her licensing fees and professional dues while Langner was volunteering.

Langner’s interests were not confined to the medical field. In fact, as a feminist, she marched in women’s suffrage rallies. Yet, she never expressed hostility, for she once told Alvin V. Sizer, “I was never aggressive because I felt that if you bided your time, something would come up. I believe that if you live long enough you’ll automatically get recognition.” Wanting to improve women’s position in the world, she encouraged the idea of women breaking out of their separate spheres by integrating the concepts of family and profession. For instance, Langner “took over as director of undergraduate health services at Vassar College when her predecessor took a maternity leave” (Curtis 3). According to Curtis, Langner confided in Merle Waxman, the director of the Vassar College’s Office for Women in Medicine, telling Waxman that she would like to see more women participating in the field. In an interview with Sizer, Langner admitted that, “There were not too many women in psychiatry then and it was a good field for us because men were not so interested in it. One obstetrician told me he always thought that people who became psychiatrists were a little nuts.” Due to her past connections with sites such as the Long Island Sound and the old Milford High School, Langner also advocated the preservation of the coastline and historical buildings in her fight for the environment. (Curtis 2-3) (Sizer 1)

As a person, Langner was absolutely amiable. People sought her for advice on many personal problems including marital difficulties, trouble with employers, and depression. Langner tried to help out anyone as much as she could. In that capacity, she sacrificed her time and offered money to patients who needed financial support for psychiatric care. “I’ve never turned down anyone who wanted to see me,” Langner said as she reflected on her earlier experiences. (Sizer 1)

“I am not old! I don’t feel old! If someone asks me for particulars I just say that I have celebrated my 99th birthday,” the vigorous and optimistic Langner informed her New Haven Register interviewer, Sizer. The process of aging seemed to be invisible to Langner, for she was quite active during her senectitude. Langner often attended one or two conferences a week in order to stay up-to-date in science. Moreover, Langner continued to walk three-quarters of a mile daily from her “white two-story house” which “overlooked the harbor” to her volunteer work at Milford Hospital and the city health department (Curtis 2). Due to this, she contracted arthritis, causing painful knees. However, she did not let that hinder her life; instead she walked with a cane. Though others tried to offer her transportation to events, such as Yale reunions, Langner steadfastly refused and chose to walk to the town center where she would take the bus to New Haven. Aside from the pacemaker that she had for fourteen years—even at her age—she was relatively healthy with few health problems. Like other elderly persons, her eyesight and hearing abilities dwindled with passing age. In order to read, she had to rely on a magnifying lens. (Sizer 1) (Curtis 2)

Having lived for so many years, she had witnessed many memorable events, such as the sighting of Halley’s Comet, which “becomes visible to the unaided eye about every 76 years as it nears the sun” (Yeomans 1). In comparison to the past, Langner felt race relations in the twentieth century society have improved substantially. During World War I, Langner vividly remembered the discrimination that her German-born parents faced. Yet, Langner felt that some old values must be preserved. She reminisced about the moments when her family gathered around the dining table at dinner. While she felt that, back in the day, alcohol was society’s enemy, she considered drugs to be the problem in her day. (McCready 2) (Sizer 1)

During Langner’s time, women were usually forced to choose either marriage or a career. Langner never married, so she was able to both accomplish a prodigious amount of work in the medical field and represent women all over the nation. Honored as Yale Medical School’s oldest alumna, she died just a few months prior to her second medical diploma as a member of the Class of 1998, the first medical class with more women than men. Langner related to Sizer that at a hundred years of age, “I make myself climb a flight of stairs everyday. I believe in a sense of humor. I am an optimist. I make a point of hoping things will get better. I’m never bored or I just doze off. I try to cultivate the young, making up for the losses I have had. I’ve said for years I was going to live to be 100.” Having enjoyed life for 105 years, Langner claimed that her secret to longevity is having good reasons for living. Even though she is no longer physically present on the face of the Earth, according to Jepson, her influence remains in the Yale School of Medicine since she donated her body to it. An ordinary Milford resident and ambitious medical student, Langner had a perspective on life: “There is always more to do than you can do.” This philosophy on life should ring loud and true in all of our hearts. (Sizer 1) (Curtis 1-2)

Simon Lake

Imagined underwater travel as a child while father experimented with flying machines

Lake passed on securing the rights to market the Wright Brother’s plane plans in Europe

“A paper nautilus, that’s all it was at the start.” (Poluhowich 3) Simon Lake’s red hair glistened upon his head, as his imagination animated his pencil sketches. Many boys dream of adventures and sunken treasure; Simon Lake was no ordinary boy, he was extraordinary. He had a vision. Childhood naivety allowed him to dream of a vessel that could function under water. He sketched out these drawings, folded them, and placed them safely in his copy of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea. (Poluhowich 3) Years later he will be known as one of the greatest contributors to submarine technology and an innovator who will forever leave his mark on history.

Even though the development of the modern submarine is accredited to John Holland, an Irish-American inventor who rivaled Lake, (Poluhowich 41) it is most improbable that the submarine could have developed to where it is without the contributions of Simon Lake, a simple man who lived here in Milford, Connecticut. Without Lake, who developed submarines mainly as an instrument of peace, the modern submarine would be blind, since it was Lake who developed the predecessor to the periscope. He also developed the twin-hull design, diver’s compartment, even-keel hydroplanes, and many more new technologies.

Simon Lake was born on September 4, 1866 in Pleasantville, New Jersey. (Ditmire website) His creativity thrived in a family that loved to invent things. His father, John Christopher Lake experimented with flying machines. Simon Lake was naturally inspired to invent. Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea, a novel of undersea travel, was the force that inspired Lake to start developing ways to make that vision a reality (Poluhowich 4).

Initially Lake met with little success in this field due to the need for military submarines, not scavengers, which were Lake’s specialty. Scavengers are submarines designed for undersea searching and salvaging. Lake’s rivalry with Holland drove Lake to improve his designs. Lake as a businessman created and operated over twelve companies on his own. These companies included: “The Argonaut Salvage Company, Lake and Danenhower Inc., Lake Engineering Company, Ltd., The Lake Submarine Company, The Lake Submarine Salvage Corporation, The Lake Torpedo Boat Company, Connecticut Building and Supply Company, Deep Sea Submarine Salvage Corporation, Connecticut Lakolith Corporation, Bedrock Gold Submarine- Machinery Company, The Submarine Exploration and Recovery Company, and The under Water Recovery Corporation.” (Poluhowich 157) These companies made him one of the leading millionaires in Connecticut. Despite this fact, Lake was horrible with money, when asked about his inability to spend money efficiently Lake only said “I’d rather die broke because I had been spending my money doing worthwhile things, than sit around cutting coupons.” (Poluhowich 84)

Lake tried his early designs in Long Island Sound with some initial success. He held about two thousand patents, and in his day, was just as ambitious as his famous rival. (Poluhowich 20) Lake worked quickly and efficiently due to his ability to sketch vehicles before development. Like most inventors, Lake first worked in generalities and did very little with specific details. Even though Lake worked tirelessly on his submarine designs, it was Holland who won the endorsement of the United States Government along with most of its contracts. That very well could be the reason that Simon Lake is not recognized globally for his contributions to the submarine.

During the Russo-Japanese war, Lake went behind the United States government’s back to smuggle parts to Russia so that his submarines could be manufactured. (Ditmire website) That’s not to say that Lake had a bad relationship with the U.S government. Lake met with the President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt, and with Franklin D. Roosevelt whom President Wilson had appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy during World War I as well as deep-sea explorer, William Beebe, and Clara Barton, the founder of the Red Cross. (Poluhowich 5) Thus, it is clear; Lake was a very well-connected man; Connections paid off when Lake’s designs were accepted in Europe during World War I, when he developed his “protector” submarine for Russia and Germany. (Poluhowich)

When working on his submarine inventions and ideas, Lake kindly shared a European office he had occupied during World War I with another set of pioneers of exploration and transportation, the Wright brothers. When developing the Argonaut Jr., the submarine that Lake is most famous for, he was finally recognized by the United States, Holland was no longer the only patented submarine visionary developing undersea craft for the government.

Simon Lake first retired in 1915. He was a wealthy man who’s “torpedo boat company was working in full tilt.” (Poluhowich 152) The monotony of retirement was too much for him; therefore, he decided to get back to work. Back at work, in 1920, he experienced economic failure. Yet he maintained a positive outlook. He was quoted saying “I quit this foolishness about retiring, went back to work, lost all of my money, and have been quite happy.” (Poluhowich 152)

Although his predictions that submarines would dominate modern warfare was laughed at and disbelieved by a majority of the officials of the United States Government, he continuously attempted to contribute his ideas reaching out many times to the President Franklin D. Roosevelt about his ideas for transport submarines. (Poluhowich 148) His ideas about a cargo carrying submarine were innovative but still the government rejected the idea, saying that a war machine was needed more than a cargo transport; this did not mean that Lake had stopped working for the government; he was just not fond of tools of war. Some say that had the rivalry between Lake and Holland taken place in a time of peace, Lake may have had more spotlights. Lake was looking to provide the world with the opportunity to explore and salvage the treasures of the sea; whereas Holland was making submarines into weapons for war. Holland was obviously going to be favored, because the United States Government needed weapons more during the war.

Lake’s accomplishments were not totally unnoticed however. Simon Lake died on June 23, 1945. He was seventy-nine years old, when tragedy struck in the form of a heart attack. He left behind three children Thomas Alva Edison Lake his son, his daughters Miriam and Margaret, and his wife Margaret.

Simon Lake’s eulogy explained that, in Simon Lake there existed the qualities of inventor, businessman, and promoter. Together these qualities created a brilliant and dynamic individual. Many of Lake’s inventions were essential to the development of the modern submarine. Today, every submarine on this planet uses the inventions created by Simon Lake. Simon Lake was a classic American inventor. He was a visionary; he accomplished wondrous feats. His ability to dream for the future will motivate generations to come. He will be remembered in history books for his inventions, and an elementary school in Milford is named after him as well. He will forever be known as an innovator, whose submarine helped to shape modern undersea exploration.

Captain Stephen Stow

Milford’s martyr

In the colonial era, Milford made its mark in the movement towards independence from Great Britain. The American Revolution was the direct outgrowth of numerous English atrocities that undermined the values of the colonists. Although the war involved all of the colonies, Milford, Connecticut, and Stephen Stow played an unforgettable part in the history defining ordeal.

In 1776, Connecticut underwent serious debate over deciding whether or not to enter the war against the British. Stephen Stow himself was caught-up in this debate. Once while attending services in the Episcopal church, where he owned pew number two, he became outraged when the minister preached a sermon entitled “Loyalty to the King”. He vowed he would never attend services in that church again (History of Milford 59-60). Even though Connecticut saw little military action, there were some minor battles at Stonington (1775), Danbury (1777), New Haven (1779), and New London (1781) (Patriots xi). Norwalk and Fairfield were also raided by the British. The Milford shore was longer in 1776 than it is currently (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009) and the Milford colonists were fearful of raids by the British along its coast. There were six cannons placed at Fort Trumbull Beach, at the mouth of the Milford Harbor(Stephen Stow 1). These cannons were stationed there to defend against any oncoming attack from the British.

On an indescribably cold winter night in December 1776, two hundred poorly clad prisoners of war were landed on the Long Island shore in Milford (Stephen Stow 1). They had been released from a British ship enroute to New London after they had been transferred from the prison ship Jersey (Stephen Stow 1) which was permanently located in New York Harbor. The prisoners of war were put ashore in Milford and abandoned, forced to wander the sleepy town. It is said that these men were being brought to be exchanged for British prisoners of war (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009) when they fell suddenly ill. The travel on the sea had been unkind to them and they suffered the ill effects of being on the sea for an extended period of time.

Close to where the men were dropped, Captain Isaac Miles and Captain Stephen Stow lived. At first, the captains were frightened by the sound of the prisoners who were walking outside. In an act of unparalleled kindness, the men attempted to alleviate the prisoners’ pain by offering them refuge in their kitchens (Stephen Stow 1). After a night of generous help, the men realized that their efforts would be in vain as the months of hardship had worn the prisoners down tremendously and many of the men had become sick with ship fever and especially the highly contagious deadly smallpox. The local townhouse was quickly turned into a makeshift hospital (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009).

There was difficulty in finding people to help nurse the soldiers because they did not want to risk the chance of being infected by smallpox themselves. One man took on this humanitarian effort despite the knowledge and would probably cost him his life. Captain Stow was willing to sacrifice his life for the greater good (Stephen Stow 1). He acknowledged the imminence of death by making a will before he left to go to the soldiers’ aid. Dr. Elias Carrington (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009) made an attempt to inoculate those who were willing to help. Stow actually served more as a nurse (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009) than as a doctor.

These prisoners of war were part of the more than 10,000 patriot soldiers that were captured during the battles around New York City. About 47 percent of the 8,500 soldiers placed in prison camps in New York died due to disease and starvation (Forgotten Patriots xi). The conditions in the camps were very detrimental to the health of the individuals imprisoned since there was a scarcity of food and medical treatment available. The army gathered testimonies from random individuals that told of the terrible living conditions in the camps which led to illness. Because of presence of so many starving people forced to live in overcrowded, hastily made prisons such as warehouses or the holds of ships, disease easily spread from person to person (Forgotten Patriots 72).

Born in Middletown, Connecticut, Stephen Stow (Lineage Book 77) was a rather ordinary individual who attained his status through arduous labor. Stow was not a native of Milford but called it his home (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009). Stephen Stow’s house was built sometime in 1680. It rested on Wharf Street which is now called High Street (Historic Houses of Early America 308). Captain Stow probably spent little time in his home since his occupation as ship master kept him at sea and thus not in a position to accept any civic or military office. Thus, there would be little told about him in the public records (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009). We do know , however, he committed his life to this noble mission of mercy and died at the age of fifty-one ( Stephen Stow 1). With his wife Freelove Baldwin Stow, he had four healthy children named Stephen, Samuel, John, and Jedediah all of whom participated in the American Revolution (Stephen Stow 1). He earned the prestigious title of “The Martyr” for his voluntary service to aid the sick prisoners of war.

Captain Stephen Stow made a valiant effort to help the sick prisoners. He was able to make the last days of a few men much better. He constantly tended to the sufferers who were very appreciative of his help. Forty-six of the almost two hundred prisoners (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009), who were sick, died. As he grew more and more tired, Captain Stow put himself into danger of contracting small pox, eventually dying as a result of it.

Today near the entrance to the Milford Cemetery, there is a monument in honor of Stephen Stow (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009). The memorial reads: "In memory of Capt. Stephen Stow of Milford, who died Feb 8, 1777, at the age of fifty-one. To administer to the wants and soothe the miseries of these sick and dying soldiers, was a work of extreme self denial and danger, as many of them were suffering from loathsome and contagious maladies, voluntarily leaving his family to relieve these suffering men, he contracted disease from them, died, and was buried with them. He had already given four sons to serve in the war for independence. And to commemorate his self sacrificing devotion to his country, and to humanity, the legislature of Connecticut resolved that his name should be inscribed on this monument"(Stephen Stow 1). Captain Stow probably spent little time in his home since his occupation as ship master kept him at sea and thus not in a position to accept any civic or military office. Thus, there would be little told about him in the public records (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009).

Besides the monument in honor of Stephen Stow, there was a representative song created in honor of the men who died. The song is “Shape the Invisible” by Martin Page. It goes: “There’s a broken man / Praying for a wounded land. / Oh why can’t we shape the invisible / For faith that’s blind / The voice of reason cries / Oh why can’t we shape the invisible/ A mother’s son / Is now a soldier marching on / He’s been told to shape the invisible/ Under poisoned skies/ The children wonder why / Our fathers can’t shape the invisible / Somewhere a small boy playing with his toys/ Someday his innocence will /Shape The Invisible”. (Stephen Stow 1)

In conclusion, it is because of the sacrifice of great men like Stephen Stow and those captured soldiers that the colonies eventually gained independence from England. Unfortunately, many of the men who died with Stephen Stow have been unidentified, though there are some names like John (Gregory Personal Interview 13 June 2009) with no last names provided. As long as we continue to inspire a new generation with their story of sacrifice, their efforts unlike their names will not be forgotten.