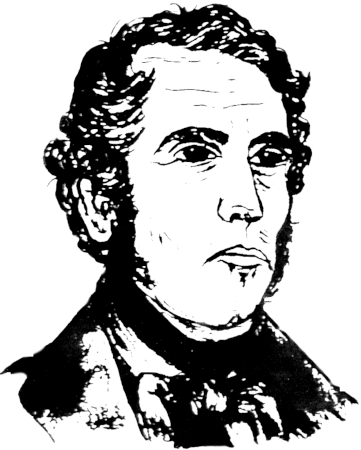

Jared Ingersoll II was born on October 24, 1749 in New Haven, Connecticut.

His was the namesake of his Tory father, Jared Ingersoll (MHOF 2019). Son Jared was a jurist, author and a delegate of the Continental Congress and a signatory to the U.S. Constitution for the state of Pennsylvania in 1789.

Although he was born in the state of Connecticut, he was more known as a state attorney general who served Philadelphia from 1791-1800.

In addition, Ingersoll was also the U.S. lawyer for Pennsylvania in the years 1800-1801 and for a short period of time he served as the presiding judge at the Philadelphia Federal District Court in the years 1821-1822.

While his father maintained a Tory proclivity until his death, Jared took to a totally different stage. He graduated in 1766 from Yale University after which he decided to travel abroad.

In the years prior to the Revolution, he was sent to London by his father to further his study at the Middle Temple - and to escape the growing political tensions in America at the time.

In the year 1776 - and no doubt a disappointment to his father at home - Ingersoll traveled through Europe endorsing American independence in disregard to the Loyalist views of his father.

As the Revolutionary Way (1776-1791) period progressed, young Ingersoll was convinced of the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation - the legal document that held the rebellious states together that was adopted by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777.

During these Revolutionary years, young Ingersoll received helpful and encouraging support from his very influential friends, helping him establish his professional reputation. His lawyerly training served him well.

Ingersoll returned to Philadelphia in the year 1778 recognized as an American Patriot - but not so by his father.

A short period of time later in 1780-81, he became a delegate to the Continental Congress. Ingersoll supported a strong central political authority.

He and others supported constitutional reforms that they believed were achievable via simple modifications of the original Articles of Confederation.

While Ingersoll did not often participate in the debates of the Continental Convention, he did attend all of its sessions. However, at the Convention, Ingersoll’s efforts to revise the existing Articles of Confederation largely failed.

Conversely, Ingersoll’s main contribution in the overall cause of Constitutional reform came not at the Convention but earlier during his extensive and illustrious legal career where he had helped define many of the principles being carried forth at the Convention.

In the end, Ingersoll joined the majority, if only half-heartedly, supporting the plan to create an entirely new U.S. Constitution approved in 1789.

Once the new national government was fully established, Jared Ingersoll went back to his profession as a lawyer. He became a member of the Common Council of Philadelphia in the year 1789. One of the very controversial cases Ingersoll entered was a landmark case in state’s rights where he represented Georgia in Chisolm v. Georgia [2 U.S.] in 1793.

In Chisolm v. Georgia, Alexander Chisolm was the executor of the late Robert Farquhar, a merchant with a shipment of clothing, cottons, linens, and blankets in 1777 that was diverted to Savanna Georgia.

There, American troops commandeered the cargo. The state of Georgia authorized commissioners authorized to pay Farquhar for his goods from the state treasury.

However, they failed to pay the $170.000 owed to him - and then Georgia erased all claims against the state after the Revolutionary War ended.

Chisolm filed his lawsuit directly with the U.S. Supreme Court meeting in Philadelphia, hiring the Attorney General of the United States, Edmund Randolf, as his lawyer. Georgia chose not to send a representative, instead offering a formal written remonstrance presented by Philadelphia’s lawyers Alexander Dallas and Jared Ingersoll.

PAGE 3

A judgement in favor of Chisolm was entered in the following February<!-18,-> 1794 term stating ”a state cannot run under the cover of state immunity to suit its own purposes.” To the defense of state’s British king-like sovereign immunity, Chief Justice John Jay opined that “the states never were in the possession of anything like independent sovereignty. The sovereignty of the nation was the people”

The court ruled that a state could be sued in Federal court by a citizen of another state.

Not surprisingly, the states objected. This was the first court litigation testing state’s rights and autonomy that would culminate in the Civil War in 1861.

Georgia’s governor, Edward Telifair, proclaimed that “an annihilation of [the state’s] political existence must follow” if anything approaching the likes of the Chisolm case decision were permitted again.

As an out, by 1795 enough states ratified the 11th amendment that declared, “The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.”

Meanwhile, the Farquhar heirs did not receive any compensation until a special bill of relief was passed in 1847 - 70 years after the original taking. The right to sue in Connecticut, for instance, is at the discretion of the state to this day.

In another early Supreme Court case representing Hylton in Hylton v. United States, 3 US 171 (1796), Ingersoll brought the first challenge to the constitutionally of a tax act of the Congress.

Sadly, he lost again, as the Supreme Court did not agree that the Constitution, Artcle I, Section 2, Clause 3, ban on any Federal “direct taxes except as apportioned to the population of a state” preventing the federal government from applying a yearly tax on an individual’s goods, in this case, carriages.

Ingersoll’s loss was the first blow against the Constitutional restrictions restraining the Federal government’s ability to directly reach into the pockets of an individual American citizen.

Eventually, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution (1913) clarified this point in stating,”The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration.”

As a strong federalist, at the turn of the 19th century Ingersoll considered the election of Thomas Jefferson to the presidency in 1800 as a “great subversion.”

As a member of the Federalist Party, Ingersoll ran for the vice presidency on the presidential ticket of New York Gov. DeWitt Clinton ticket in 1812. James Madison and Elbridge Gerry defeated them.

He also served as the presiding judge at the Philadelphia Federal District Court in the years 1821-1822.

At the end of his life, this Connecticut man - Jared Ingersoll II - was buried in Philadelphia’s First Presbyterian Church cemetery in 1822.