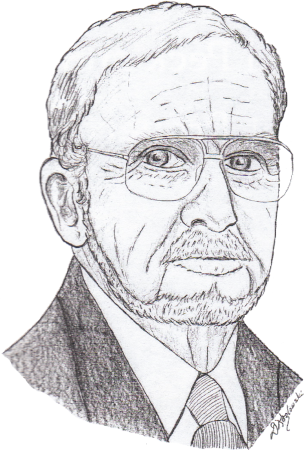

Hometown boy made good

It was on July 18, 1906, that Joseph Anthony Foran entered the world in Meriden, CT, the third child of Anna (O’Connor) and John Valentine Foran. His early life can be most accurately described as “ordinary,” as siblings Henry, Grace, Elizabeth and Paul joined him by 1917. As the family grew in size, the Forans moved from Meriden to Milford to Stratford, back and forth in a quest for an apartment that was less expensive than the last.

As a result, Joe was never in one town long enough to learn much in school. Besides, he was too tired from the before- and after-school jobs that he had by the age of 9 to care much about learning, as his father was often out of work, and someone had to supplement the family income. By the time he reached Milford High School, some teachers felt he was rather “educationally challenged” – and that coincided with another round of unemployment for his father. Joe finally quit school at age 15 and went to work in a meat market to pay off the family’s accumulated debt at the store and to provide food for the family of eight. By that time, Joe had lost two siblings, a brother, John, who had died in infancy, and Mary Alice, who died in 1925.

Joe’s Aunt Gertrude, from his mother’s side, was a teacher and an early influence. She encouraged Joe, no matter what anyone thought of his abilities, to read and acquire knowledge. He was fortunate as well to have “Doc” Pearson, a teacher at The Milford Preparatory School, befriend him, and they had many lively conversations about history and literature. One day, when Joe was looking a bit forlorn, Doc asked him, “What is the matter?”

“Doc, I was just thinking – is this all that there is for me?”

“No, Joe, if you’re willing to work at it you can go to college. You’re a very smart young man despite what you’ve been told.” Joe took those words to heart, and was tutored, tested, and tutored some more by Doc and other teachers from the prep school. Their goal was to have Joe enter West Point. Even though Joe did not have a high school diploma, he was able to sit for the exam, and received the highest score; all the teachers were sure that he would get the appointment. But soon the news came that the appointment had gone to someone whose family had more influence and stature. To say that Joe was disappointed is an understatement. However, Doc Pearson pulled him out of his funk, and Yale became the next aim. Joe passed the entrance exam at the age of 26, and in the fall of 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression, he entered Yale. While he was a resident of Trumbull College for only two years and was eight years older than most of his comrades, the friendships he made were life-long, and sustained him as he grew old. In June 1937, Joseph Foran graduated from Yale with a degree in history.

As his Yale days wound down, one of his history professors asked, “What are you going to do after graduation, Foran?” He replied, “I’m really not sure – maybe law school.” The professor replied, “You’d make a great teacher, Foran. Give it some consideration.”

In fact, he gave it more than a little consideration – as in September of 1937 he came to teach in his beloved Milford. He was a teacher and teaching principal in several grammar schools and also taught in Milford High School. He had eleven years of working with children, parents, teachers, and administrators, and loved his work.

However, by 1946 the Foran family was growing, as children Paula and Joan were six and four, and he had decided that he would not earn enough money teaching to provide for his family.

Foran had been accepted at Yale Law School and was enrolled to start in September 1946. Fate then intervened, as in the summer of 1946, then Superintendent of Schools Lester Maddocks died very suddenly, and Foran was promoted to Superintendent.

Imagine going from a high school dropout to becoming the head of the school system! Now Foran found himself the boss of those who thought him “challenged,” of those who called him “Joey” even though he was an adult. Quite an irony! Yet, Joe never gloated or laughed at them, but his blue eyes did sparkle when he talked about how he felt on the first day in the “boss’s seat.”

He often said that his early educational experience helped him relate to students who had difficulties, and aided him when giving teachers advice about students. He was also keenly aware that with the encouragement and help of a mentor, one could go far in life. He used to say to his daughter, Monica Foran, “People sometimes say they pulled themselves up by their own bootstraps, but that is rarely the case. There is usually a helping hand, but it’s much more dramatic and self-satisfying to say you did it alone.” What he left out was his own determination to prove that Doc Pearson had made a great decision by having faith in him. His daughter, Monica, sometimes thinks, “What would life have been like for us without the guidance that Doc Pearson showed my father?” – mulling that perhaps Foran’s life can be likened to that of Jimmy Stewart in the holiday classic, “It’s A Wonderful Life.”

In leadership studies, professionals talk and write about two aspects that are most important: results and attributes. The results of Foran’s tenure as superintendent were admirable. He believed in the neighborhood school, and used the art of persuasion as well as factual data to create a school system that truly served the community as a whole and within its parts. To accomplish the goal, he first visited any parental group and civic group he could find. The Milford Citizen has very small articles about him visiting these groups – no headline news about decisions he made early on.

Foran knew he had a lot to learn from those around him, and he used that first year to gather knowledge, share his vision, and let the townsfolk know he was approachable. He approached the PTAs, local church groups, non-profit organizations, and governmental committees to explain why the neighborhood school was a great plan, and how it would affect the children in a positive way, at the same time showing people his personal commitment and extraordinary dedication to creating a positive atmosphere for learning.

It was no small task to convince the townspeople that it was necessary to buy land as the future site for a school, but he succeeded with the help of others, of course. Reading through back issues of the Milford Citizen, it is remarkable at the number of parcels that were purchased during his leadership and to name the schools that soon sat on these sites: Point Beach (now a condo site), Calf Pen Meadow, Matthewson, Live Oaks, a new Milford High School (now the Parsons Complex where the Milford Hall of Fame is located), Jonathan Law High School, Foran High School, Kennedy, Orange Avenue, and Kay Avenue (today West Shore Middle School), as well as renovations and additions to other schools.

At the same time, Foran hired skilled professionals as teachers and encouraged them to reach toward a higher goal – to earn a Masters and Administrative Certificate so that they could advance within the system. Former Milford school principal and superintendent of schools Bob Blake has acknowledged that Joe Foran was one of the guiding forces in his life: if you worked hard and took advantage of the education available to you, you could rise within the ranks of your own school system, and provide continuity and accumulated knowledge of students, parents, faculty, and administrators.

Is hiring from within the system always the best way? It certainly seemed to work for the Milford community at that point in time.

At the same time, Foran’s attributes were equal to his achievements of educational excellence for Milford. His daughter Monica said she “hardly knows where to begin to describe how easy he was to be around. He was never judgmental; he had made mistakes in his life, and afforded others their chance to make their own without chastising them when they came to him for guidance. He had a wonderful sense of humor that he was willing to share. He was respectful of others. He had a fabulous memory for names, places, stories, historical events, and the successes and tragedies that were part of people’s lives.

“People always tell me about the high school reunions my Dad attended. The folks would cover their name badges, and say, ‘Ok, Mr. Foran, who am I?’ And he would say, ‘Fannie Beach, grade 4, row 2 – you’re John Smith!’ And he would be right! He could still do this at the age of 90; each child had been important to him, and made a mark in his mind. He absolutely hated it when he could not place a face with a name, but that was a very rare occasion.

She continued, “I personally believe that one of the greatest reasons for his success was his ‘hometown boy made good’ life story, and that he was satisfied to be a big fish in a small pond rather than a small fish in a big pond. He loved Milford, and the job was not a stepping-stone to a higher-paid job in some other town down the road. He was visible and approachable. I remember grocery shopping at the A&P that stood next to the railroad station. We would do an hour’s worth of shopping – and he’d do an hour’s worth of talking with people. It didn’t matter what their station in life was – in my Dad’s eyes, all people were equal and deserving of his time and energy.

“In my entire childhood, I never heard derogatory remarks about anyone’s race, religion, ethnic background, or mental acuity. As I grew into adulthood, I realized how fortunate I was to be brought up in a house where neither parent disparaged others; while it is said that we all have our fears of one group or another, my parents taught us that we needed to know a person’s background and personal traits before passing judgment. A person had to prove him or herself unfit, untrustworthy or unpleasant; my father wasn’t suspicious of or reticent toward anyone at first meeting.

“When people came to apply for teaching jobs, only the credentials and letters of recommendation were important; a person’s race or religion was of no consequence to him. Applicants needed to demonstrate a desire to help children and have an affinity for the role of parents in the education of their children. When Miss Richards applied for a job in the system, the local women’s group from the Protestant church made an appointment to see him. He was apprehensive, for Miss Richards was African American, and he was set for a confrontation. Lo and behold, it was anything but that; the women wanted Miss Richards hired. Dad was always grateful for this support and delighted with the knowledge that Milford had people with open minds, open hearts, and the ability to suspend judgment until someone proved him or herself unfit for the task.

Monica Foran continued, “Just to demonstrate what I mean by equality and understanding other people’s hardships, I want to tell a story about the Ramos family. At my father’s wake, Edmund Ramos said that his life and his siblings’ lives were changed forever by the intervention of my father. Edmund’s parents were immigrants and owned a farm in town; they had 12 and ½ children on the day that the elder Mr. Ramos died very suddenly and unexpectedly. My father heard the terrible news and realized that Edmund’s mother needed some help as she tried to provide for her children. As Edmund Ramos describes, it, ‘We were sitting at home, trying to figure out what we were going to do, and a knock came at the door. My mother opened it, and there stood your father. He said, ‘Mrs. Ramos, I am so sorry for the tragic loss of your husband. What is it that I can do for you?’ My mother said, ‘Mr. Foran, I need my boys at home to work this farm. I need to have them quit school.’”

That was the last thing Joe Foran wanted to hear because he knew personally the toll that would take on a young person. He told Mrs. Ramos he would try to work something out so that the boys could stay in school and still tend the farm. He went back to his office, called the State Dept. of Education, and together they devised a plan to have the Ramos children attend school four hours a day, then go home to work. He laid out the plan for Mrs. Ramos and was very honest.

“The boys will have to go to school and also do their homework every day; they will not be excused from this part of their education,” he said. “Will this work for you, Mrs. Ramos? Will you see to it that they do their homework? It will be hard for them – and for you - the days will be long.” Mrs. Ramos instantly agreed.

As Edmund Ramos told Monica Foran this story, he began to cry and laugh at the same time. “I can remember saying I was too tired to do my homework, and my mother would say, ‘Mr. Foran came all the way out here without being asked and has given you a future. You respect him. Open those books and do your homework.’ And then she’d slap the back of my head to let me know she meant business. If it hadn’t been for your Dad, none of my sisters or brothers would have succeeded in life – and we all finished high school, went to college, and have professional lives. He was a great, great man.”

Monica noted that “This story always makes me cry because my father never told it about himself; I had to wait until he died to hear it. I would have loved to tell him how much I admired him for reaching out to someone in such need without being asked.”

As readers can tell by now, Joe Foran lived by the words of the Golden Rule, “Do unto others as you wish them to do unto you.” There was nothing complicated about Joe Foran’s ethics or values. Bob Blake told Monica Foran about a saying on the wall in the “Yellow Building” on River Street, now the River Park senior housing complex, where there was a plaque that read, “I complained about having no shoes until I met a man with no feet.” If all of us remembered that story, imagine how much less complaining we would do, and how much less complaining we would hear?

“My Dad was not a complainer, even though I am sure that he had plenty to complain about. He handled those who gave him the most difficulty by turning the other cheek. This doesn’t mean he became a victim of some sort of abuse; it means he could separate a person’s human qualities from his or her ideas and defend his own thoughts with convincing data and intellectual argument. He would not ignore the slight or argument; he just knew the difference between conflicts of opinion and conflicts of personality. Some of the people he respected most were often those with whom he had a conflict of ideas.

“He once said to me, ‘One of the most difficult things in life, Monica, is to realize that some people consider a criticism of what they do as a professional to be a criticism of who they are as a person. If you remember that there is a distinct difference between who a person IS and how he or she PERFORMS at a job, you will get along. If you ever have to chastise a person for a mistake on a job, remember to start out with a compliment – that lets them know that you respect the person even if you need to criticize the performance.”

Why was the east end high school in Milford named after Joseph Foran? It was because he gave respect, admiration and love to people of all ages, races, and creeds; and because he built a school system worthy of the citizens of Milford. In return, he was well respected, admired and loved as a person. He was known to be honest, self-effacing, quick witted, and fair. Many people in town had known him for decades – from his youth, his time in the meat market and through his days at Yale, into his almost three decades with the school system. He shopped locally and was accessible, sincere in all his associations. He was a man who went from meat cutter to educator, but never bragged or thought too much of himself. He gave others credit where credit was due; he often said his job as superintendent was made easier than it could have been by the dedicated work of administrators, teachers, parents and students. In today’s leadership scholarship, he would be called a proponent of shared leadership: he never hogged the glory.

After Foran left the school system, he served on the Board of Education, and was a source for any newspaper person who cared to call. Frank Juliano of the Connecticut Post once said that one of his saddest days was the day he exclaimed, “Oh, I’ll call Joe Foran” – and then remembered there was no Joe to call. He became a town celebrity of sorts – not in his own eyes, but in the eyes of others. It was wonderful for his family to see because he deserved to remain of value and a source of inspiration to others.

To sum it all up, Joe Foran had a great rapport with students, teachers, administrators, parents, and civic leaders on both the local and state level. He understood that children’s lives were often not easy; he knew there were events behind the scenes that caused them heartache, anger, and sleepless nights. He evaluated those who worked with him on their success in their jobs, not on their personalities. He listened to parents who had problems with their kids or problems at home, and tried to help them in any way he could. He was dependable, even-tempered, quick with a compliment, and kind. He didn’t make excuses for people’s behavior and he believed in discipline, but the punishment fit the crime within the confines of the school rules. He tried to help people through their trials and tribulations, listening carefully and trying to suggest solutions without telling them what to do. In every sense, Joe Foran was a self-made man.